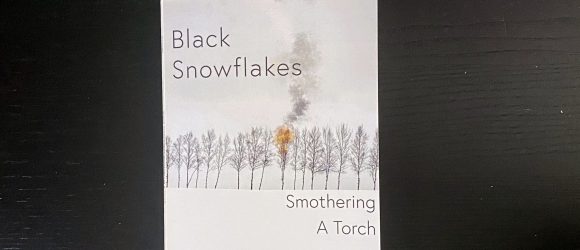

Review: Black Snowflakes Smothering A Torch: How to Talk to Your Veteran – A Primer by Ryan Stovall

- At November 19, 2022

- By Bob Howe

- In Poetry, Reviews

0

0

“having shot children” is the first line of the first poem in Ryan Stovall’s poetry collection, Black Snowflakes Smothering a Torch. War didn’t let him off easy, and his book isn’t letting us off easy.

Stovall served as a Green Beret (U.S. Army Special Forces) medic during the war in Afghanistan. Twice wounded, he has seen the elephant and been seen by it. He styles his collection a primer for civilians to speak to veterans about their experiences, but the poems also hold a mirror up to civilian life—and not in a flattering way:

I want to win the New way

the urban stylish civilized way

the learned pretentious academic way

the polite two-faced ingratiating way

the slap you on the shoulder

shoot you in the back way

if it will keep my memories at bay

then I will smile and smile

and be a villain

This is an intimate book. Stovall doesn’t digest war for the reader: he brings it back raw and sets it on the kitchen table, burned and red and leaking blood on the place settings. If you’re going to “talk to your veteran” (as he styles it), you need to taste some of war’s melancholic illogic, brute humor, and horror unfiltered. The title poem—the longest in Stovall’s collection—is a chain link fence of associations that marks the boundary between the civilian world and the world of war. Like most great poetry it is felt rather than understood: a shock wave that can leave the unarmored reader invisibly changed:

even some of us pipe-hitting HALO studs

return afraid of everything

from sudden movements

to failure

from disapproval

to dissecting aortas

to displaying cowardice

or courage

This book is not war tourism, and it is not easy—hardest, it seems, for Stovall himself (“some rocks should never be pushed aside”). His ambivalence about seeing and telling is part of what gives his poetry power and depth. Black Snowflakes is deeply humanistic approach to war writing that does not explain nor condescend. As poetry, as truth telling, as confessional, as jeremiad, this collection will live long in the attic of your soul.

Review: We Are All Completely Beside Ourselves

- At April 10, 2014

- By Bob Howe

- In Reviews

0

0

We Are All Completely Beside Ourselves by Karen Joy Fowler

My rating: 5 of 5 stars

First of all, ignore the blurb: while literally true, it fundamentally misrepresents what the book is really about.

If you belong to a writer’s organization, you’re exposed to a lot of debate about the value of awards. On literary merit, the spectrum of opinion runs from “popularity contests” to “deeply flawed processes” to “they got this one right.” Whether awards help sell books is likewise a contentious topic.

When We Are All Completely Beside Ourselves won the PEN/Faulkner award, the book wasn’t on my radar. If not for the burst of publicity in the wake of the award, I would likely have never read the book. And what a shame that would have been.

Fowler’s book is about loss, grief, and the plasticity of memory. It’s deeply felt and brilliantly executed. If you care at all what drives some people to be writers (spoiler: not the money nor adulation), then you should read this book.

The Reasonably Adequate Gatsby

- At September 20, 2013

- By Bob Howe

- In Reviews

0

0

[Obligatory Spoiler Alert]

The critics are not in love with the latest film incarnation of Gatsby. Lenny Cassuto, a professor of English at Fordham and fiction writer himself, believes the curse of Gatsby movies is that the audience has read the book, and has what he, Cassuto, calls “individuality of response;” everyone has their own Gatsby in their heads. It’s an interesting conceit, but I don’t buy it.

If “individuality of response” didn’t kill Peter Jackson’s execrable Lord of the Rings, a trilogy that much of the audience can quote in large snatches, then it seems an unlikely explanation for the Gatsby Curse. In any case, most books are Rorschach tests. Lichtenberg said, “A book is a mirror: if an ape looks into it an apostle is hardly likely to look out.” I think that sums up the field of literary criticism fairly neatly.

I sat through Baz Luhrmann’s Gatsby today, and mostly found it pretty diverting—even at two hours and twenty minutes. It was visually stunning. I thought DiCaprio was a fine Gatsby, and Tobey Maguire a likeable amanuensis. I take El’s word that the film is reasonably faithful to the book: though I read Fitzgerald’s novel, I recalled none of it as the story unspooled on the screen.

I think the reason The Great Gatsby is impossible to film, or at least why critics think so, is because they’ve already seen the iconic version. It’s called Citizen Kane. Like Gatsby, Citizen Kane is the story, told in flashbacks, of a man who amassed money and objects in the pursuit of love, only to die alone and misunderstood. Both have their sympathetic (if less great) Boswells, both live in ornate mansions, having risen from grinding poverty, and both try relentlessly to claw back a happier past.

About halfway through the film I realized that every close up of DiCaprio reminded me of Orson Welles: the captain of a doomed ship underway at night in a fog, chasing fairy lights with increasing desperation. In neither case do the main characters’ rags-to-riches transformation succeed in bringing them the desired consummation. Authenticity, it seems, is what the universe requires, and what Gatsby and Kane have forgone.

Though The Great Gatsby was published 16 years before Citizen Kane was filmed, I think every screen version of Gatsby stands in the (considerable) shadow of Orson Welles. Both DiCaprio and Luhrmann would know at least a little of Welles’ untidy personal life. (John Kessel captures a rigid, self-destructive Welles painfully well in the short story “It’s All True.”) As an actor, DiCaprio must have seen “the greatest movie ever made,” and Luhrmann certainly would know Citizen Kane inside and out.

The considerable gravity exerted by Welles’ film, his portrayal of Kane, and his larger-than life, may well have bent the latest Gatsby and its title performance into familiar planes. If nothing else, Citizen Kane is a staple of film criticism. The critics may not like Gatsby, and especially this Gatsby, because every tight shot of DiCaprio’s anguished face would be moment of uneasy déjà vu in the seats. It is one thing to know where the arrow will land before it leaves the bow—tragedy often possesses a grim inevitability; it’s another thing to follow the same missile over the same course again and again.

So we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past.

F. Scott Fitzgerald, The Great Gatsby

Leonard Cassuto, “Are The Great Gatsby Movies a Lost Cause?”

John Kessel, “It’s All True” from Some Like It Cold