Night Crossings

- At February 08, 2015

- By Bob Howe

- In Blog Posts, Poetry

0

0

a fast northbound train

sheds an icy comet trail

the winter station

#

everyone has those nights

when memory chases desire

afoot in terrain

of comforting terrors

#

the night crossing

of necessity

oars unshipped,

unpoised

over a rushing skin

of black water

fleeing people

of a book redolent

of blood and ash

vision strained to a far shore

time shrouded and

memory wooded

#

the color of death

is white, leaden winter sky

the absence of depth

Rearranging Deck Chairs

- At November 30, 2014

- By Bob Howe

- In Blog Posts

0

0

I discovered science fiction as a teenager in the late 1960s and early 1970s. That is, written science fiction — not the inane, derivative crap served up under the rubric “Sci-Fi” on television and film. Many of the books I read concerned themselves with the future of the human race, taking current trends and extrapolating them to their logical conclusions. “What If” stories, as they’re sometimes called.

A particular topic of interest to writers at the time was the population explosion. It was before the global population had topped 5 billion, but anyone who didn’t have their head in the sand could see that we were headed that way, and that it wasn’t going to be pretty. There was Harry Harrison’s Make Room, Make Room (and its dreadful film incarnation Soylent Green), Isaac Asimov’s Caves of Steel, Robert Silverberg’s The World Inside, and John Brunner’s brilliant Stand on Zanzibar, to name a very few of a huge sub-genre.

Overpopulation of the Earth was on many people’s minds, of course, not just those of science fiction writers. Dr. Paul Ehrlich published The Population Bomb in 1968, making a huge splash. (Ehrlich’s book and ideas are the subject of a PBS show: “Paul Ehrlich and the Population Bomb,” from KQED Television, San Francisco.) The modern environmental movement, born in the 1970s, explicitly linked population reduction with environmental conservation.

Since the 1970s, however, we seem to have developed a collective amnesia regarding the problem of overpopulation. The problem is obviously worse than ever, yet it receives no mention from the media, or from our feckless elected representatives. Environmental groups tiptoe around the issue while making pitches to save this or that “charismatic megafauna.” Pandas, whales and even wolves bring in the fundraising dollars. Pitches to reduce the population are more controversial and less profitable.

So what happened? According to the International Programs Center, U.S. Bureau of the Census, the total population of the world on April 14, 2001 is 6,141,093,882. Here’s a little context for that number; a short history of world population:

Year CE Population

1 170,000,000

1000 813,000,000

1850 1,128,000,000

1900 1,500,000,000

1950 2,400,000,000

1986 5,000,000,000

2001 6,141,000,000

[2014 7,277,822,663]

In other words, it took 1,949 years for the world population to reach 2.4 billion, but just 51 years for it to reach 6.1 billion. If this is not the definition of an ecological crisis, I don’t know what is.

It is true that residents of industrialized nations, and especially the United States, consume vastly more resources per capita than people living in the Third World (a problem we’ll return to shortly), but there is an irreducible minimum amount of resources that each person consumes regardless of location and living conditions.

Any environmental effort that does not include reducing the number of human beings on the planet is just rearranging deck chairs on the Titanic. In fact, the Titanic metaphor doesn’t go far enough. If we exceed the Earth’s carrying capacity, there will be no rescue vessels to save us from the frigid North Atlantic. The lucky or privileged few who have a seat in a lifeboat, if they survive at all, will do so in circumstances so reduced that the most hardscrabble Third World existence will seem luxurious by comparison.

All of the foregoing seems painfully obvious to me. The Earth has finite resources. Other species that multiply beyond the environment’s carrying capacity are reduced by disease and starvation. Humans are not immune to the laws of nature. The facts and figures above are easy to come by. Why aren’t people crying from the rooftops?

Well, you can’t rule out ignorance. We live in a country where more than forty percent of adults believe in some aspect of creationism — 100 years after Darwin and warehouses of fossil and genetic evidence notwithstanding. If you don’t have a grasp of the most elementary facts of biology, you’re not likely to be an ardent advocate of population control.

The influence of religion cuts both ways in the population debate. There are Protestant sects in the U.S. that advocate responsible family planning. On the other hand, the Catholic Church and many fundamentalist Protestant churches consider birth control and abortion to be sins. In the interest of brevity, I will forego a riff on the obvious lunacy of an organization of (ostensibly) celibate men setting rules for birth control.

There is also the quasi-religious appeal to what is “natural.” It is natural for people to have children; it is unnatural for the government to try and reduce the birthrate — look at the Chinese Communists’ ruthless enforcement of family planning laws (one child per couple). Well, the Chinese do everything pretty ruthlessly. There are ruthless ways to lower the birthrate, and humane ways to do so. As far as what’s natural: smallpox, diphtheria, cholera famine and intestinal parasites are natural, too. You rarely hear advocates of natural population control (ie: none) wax poetic about tapeworms.

There is the craven performance of our own government to consider. Congressional Republicans have instituted “gag rules” that prevent physicians who receive Federal aid from discussing abortion with patients. Congressional Republicans have also killed family planning funds in foreign aid packages, and imposed bans on funds for contraceptives in foreign aid packages to the very nations where contraceptives would do the most good.

It gets worse. Under George W. Bush we are happily rolling back two decades of environmental law in the interests of big business. The administration hardly even offers a pretense of environmental accountability. Is it because Bush and his advisers are bad people? Yes. They are probably the worst band of thugs to steal power in my lifetime. But the administration couldn’t undo environmental law without the collusion of most Americans.

In 1992 I lived in Portland, Oregon. It was the year that Spotted Owl habitat in the Willamette National Forest was protected under the Endangered Species Act. The timber companies screamed for blood, of course. Loggers identified with their employers’ interests, since that’s where their paychecks came from. It was common to see “paid for with timber dollars” stamped on personal checks; and the slogan “People, Not Owls” was ubiquitous. It was painful to hear the loggers’ defiant self-pity in television interviews. Sometimes the interviewer would ask the logger what would happen to their jobs when all the trees were cut down. In the weeks before they were well-prepped by timber company flacks, that question often provoked a vacant, helpless stare, as if the logger had been pithed.

Sooner or later, if you log enough trees, they’re all gone. Of course the timber companies replant seedlings, which in a hundred years will begin to reach the size of the trees they’ve cut down. In the interim, all the animals that lived in and around the trees are killed. The timber companies like to say these animals are “displaced,” but that’s disingenuous, to say the least. If you squeeze twice as many animals into the same amount of habitat, most of the surplus dies of starvation or predation, or fails to reproduce.

Clearcutting swatches of forest produces other effects that magnify the loss of species. From island biogeography we now know that two 1,000-acre tracts of forest separated by a logging road or clearcut are not the same as one 2,000-acre habitat. The split tracts support fewer animals and fewer species. Worse, in some cases so-called keystone species are eliminated. Keystone species are “plants and animals that might be especially crucial to maintaining the cohesion of an entire ecological community over time.” (Quammen, Song of the Dodo, p. 541).

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, in 1998 there were more than 1.6 million new housing starts. In the decade from 1988 to 1998 there were more than 13.5 million new housing starts. Assuming an average lot size of one acre, that many houses would cover 21,093 square miles — an area slightly larger than the states of Massachusetts, New Hampshire and Rhode Island combined — and that’s without factoring in streets, highways, businesses, schools, parking lots and municipal buildings. Some percentage of these housing starts are in urban or suburban areas where the native species have already been exterminated. But too many are encroaching on previously wild habitat

It doesn’t matter to the affected species if you’re logging or building real estate developments or damming a river. Once they “wink out,” in Quammen’s ominous phrase, that’s it. Other species might evolve to fill that niche, assuming the environment was restored, but probably not in any time scale meaningful to humans.

According to Zero Population Growth, “A very small proportion of the population consumes the majority of the world’s resources. The richest fifth consumes 86 percent of all goods and services and produces 53 percent of all carbon dioxide emissions, while the poorest fifth consumes 1.3 percent of goods and services and accounts for 3 percent of C02 output.”

In that short paragraph is buried the key, I think, to our ability as individuals and a nation to ignore the long-term good for short-term gain. The way average citizens collude with the worst policies of our government amounts to a pyramid scheme. The vast majority of workers in the world live on wages far below the U.S. poverty level. The relative affluence of Americans rests on the back of plentiful cheap labor. Plentiful cheap labor requires an ever-growing population to insure supply outstrips demand. A pro-population growth stance on the part of big business and government ensures a steady supply of marks for the ponzi scheme.

Business not only wants cheap labor, of course, but ever-expanding markets. If the population were static or (horrors!) shrinking, who would buy the 1.6 million new homes constructed in 1998? In 1999 Americans bought 17.4 million new motor vehicles — production lines were turning out a vehicle every two seconds, 24 hours a day, 365 days a year. Worldwide personal computer sales were between 112.7 and 113.5 million units in 1999.

We are, in effect, consuming the ship in order to live comfortably now, with little thought for what we’ll do when the last spar and rib are fed to the fire. The closer we are to the top of the market economy pyramid scheme, the greater comfort we have at the expense of the workers in steerage. Big business, through its captive politicians, shouts orders from the bridge that make sense only as long as no one is looking over the rail and watching the water level rise.

On the promenade deck, the ship’s band is rehearsing a catchy little tune: Nearer My God to Thee.

Here’s hoping your deck chairs are comfortable deck chairs.

###

Originally published on the Fetish Weather Forecast

Monday, April 16, 2001 | Volume 5, Number 14

Writer’s Workshops: Under the Black Flag

- At August 10, 2014

- By Bob Howe

- In News

0

0

My essay, “Writer’s Workshops: Under the Black Flag,” is live at Black Gate.

I actually once said to a fellow writer, “The best thing you could do for art is cut off your hands and bury your typewriter.”

Beyond the words themselves, it’s hard to know what’s worse about this: that I said it to someone I’m sure I liked or that I can’t remember to whom I said it.

I know it was at the Clarion Writer’s Workshop in the summer of 1985, then held at Michigan State University in East Lansing. I knew it was someone I liked, because I liked every one of my fellow workshoppers. As I got to know the 16 other participants, I felt these are my people!

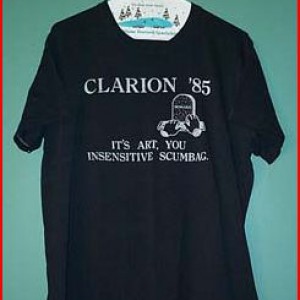

The context for the remark was a workshop session. For those unfamiliar with the format, everyone in the workshop delivers an oral critique of a manuscript handed out — and one hopes, read — in advance, then the author responds. Clarion workshops are machines for producing pithy one-liners — often put downs — the best (worst?) of which are memorialized on tee-shirts printed in the last week or two of the workshop. [More]